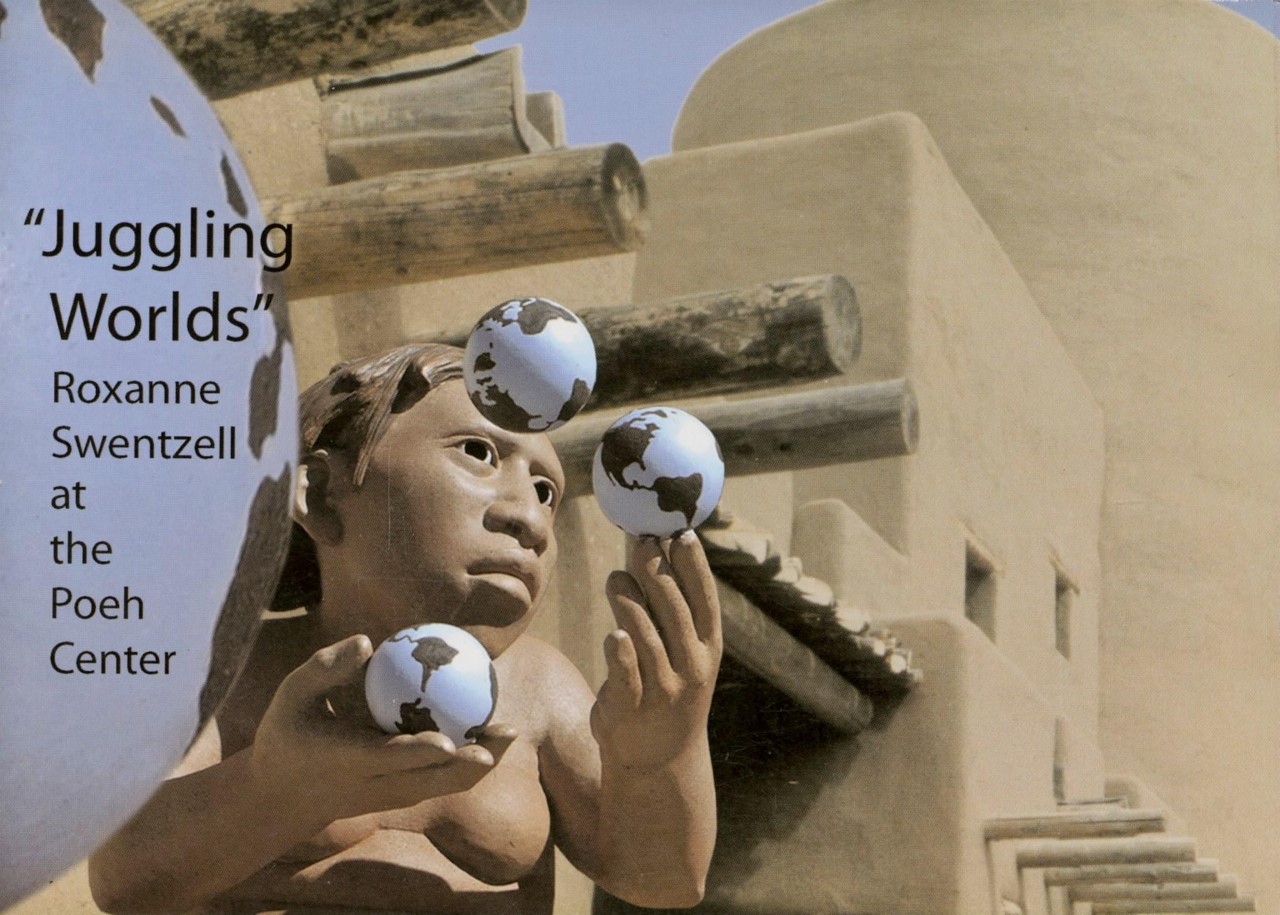

Roxanne Swentzell at the Poeh Museum

August 20 – November 28, 2003

Roxanne Swentzell at Mid-Career

by Mateo Romero

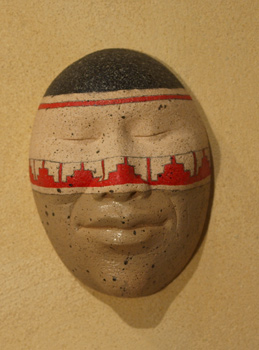

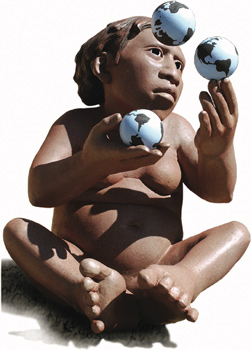

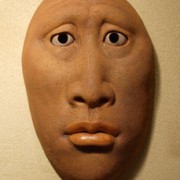

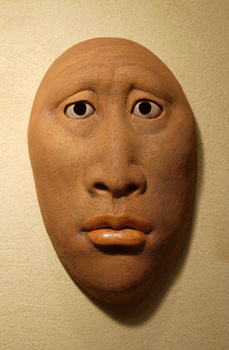

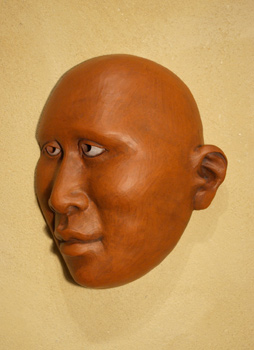

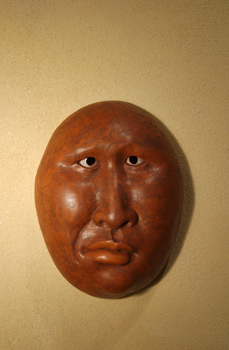

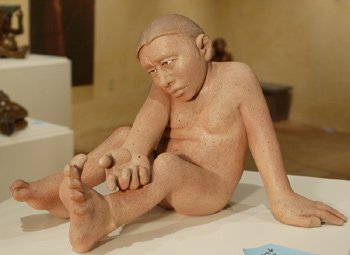

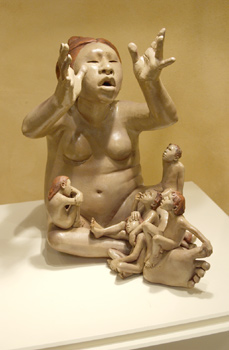

Rhythm, balance, emotion, shyness, children, love; these are words I use to describe the sculpture, art and life of my friend Roxanne Swentzell. If I were to respond to the essence of her work, it is the mastery of the three dimensional form within the emotive context of the human figure.

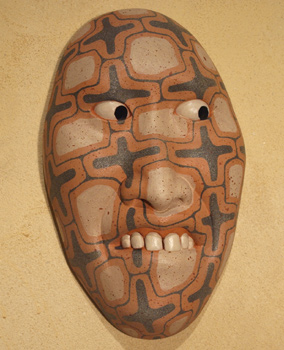

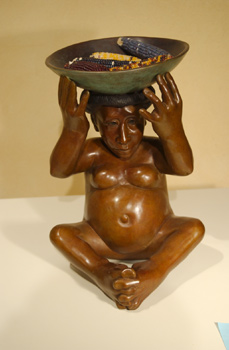

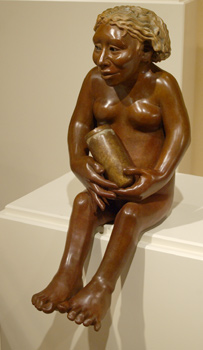

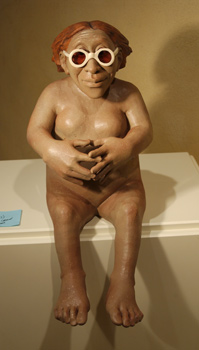

Rox’s work emotes. Figures of clowns, old men and women, and children twist, turn, undulate, laugh, cry, repair themselves, interact with each other, and love each other. It is through this intricate balance of elements that her work reaches our humanity and engages us as both audience and participant.

One of the most fundamental concepts in Pueblo ideology is the harmonious balancing of opposites. The life and work of Rox can be seen as a complex interplay between opposites or polarities. Although she has a mainstream art education, her work and sensibilites are firmly grounded in a sense of Pueblo identity. Her work is in demand in a blue chip commerical art market, but it is clear that the integrity and personal vision of the work comes first. Risk taking, experimentation, and content-based narratives in the work defy the simplicity of the lowest common de- nominator of the market place. It is the breath of sincerity that emanates; appeal is based on a shared emotional connection between artist and audience.

In a structuralist analysis of Pueblo culture the idea of balancing opposites is a central theme. Summer/Winter clans, life/death, mainstream world/Pueblo world, personal integrity/art market. Taking this comparison further, we have a series of binary opposites, which seemingly define each other in their intraction with each other. But, the interaction between binary opposites creates a third relationship, as in the classic example of Summer and Winter clans re-integrating for the brief space of the Pueblo feast day in the plaza. This triadic relation- ship can be seen as a central part of the meaning of her sculptures.

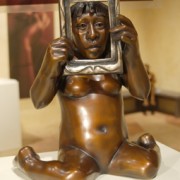

In the regional Southwest, where Native art is synonymous with Native American subject matter, Rox’s work crosses the acceptable paradigms of Indian art into content-based art with specific intellectual meanings. A particulartly strong series of work in this vein is her sculpture dealing with the female nude. Within her signature style use of the de-co modification of the female body, male gaze, and gender identity. The power of this type of content-based work transcends regionalism placing it squarely in the realm of the best of mainstream art.

Perhaps most important of all is Rox’s search for home, her diaspora traveling from village, pueblo, and art school; searching for a literal of metaphoric center of sipapu for her art, family and life. In this journey Rox has been both a student and an instructor at the Poeh Cultural Center, as well as working on a garden project at the Poeh. Those of us who have been touched by Roxanne as she walked with us awhile on her journey, think that ultimately home is where ever her childern and her clay creatures eat, love, quarrel, and lay themselves down to sleep at night.